Alan Dowds enlightens us…

My Dad, Jim Dowds, started his working life as a car mechanic, though by the time I came along, he had moved on to work at the IBM computer factory in Greenock. Amazingly, back in the 1960s, computers had a lot of mechanical parts in them – solenoids, relays and the like – meaning hands-on practical skills were useful to the American mainframe maker.

He always worked on his own cars though, so I grew up watching him maintain and repair a series of 1970s and 80s motors – from a Ford Anglia and a couple of Austin Allegros to a Vauxhall Viva. Then, when I got my first motorbike – a Honda CG125 – he had the tools, the skills and the confidence to help me learn how to fix the bloody thing. Six months later, I had passed my test and had a decent summer job, that let me buy a big bike – a Kawasaki GPz550, which felt like an utter rocketship. Of course, I soon blew that up, and was stripping it down on the kitchen table, with help from my old Dad again.

Enjoy everything MSL by reading the monthly magazine, Subscribe here.

Now, though, he was amazed by the hi-tech kit before him. The GPz550 engine was an old design by 1990 when I bought it, with air-cooling and two valves per cylinder – but it had double overhead camshafts, four individual carburettors, CDI ignition and 130bhp/litre performance. By comparison, the 1960s and 70s cars he was used to had pushrods, or maybe a single overhead camshaft. They had points ignition, one rather nasty carburettor, little in the way of performance engineering at all, and made maybe 70bhp from a 1600cc inline-four.

Over the next couple of decades, I worked away on my own bikes – and my own cars. And that hands-on experience confirmed that motorcycle engines were miles ahead of cars. The Japanese bikes I owned had engines with all-aluminium crankcases and barrels instead of cast iron blocks, four- or five-valve heads instead of two, and electronic ignition instead of points, coil and mechanical distributor. Okay, I was dealing with normal family cars, not high-end sports cars, but the point remained. Car engines seemed to be designed with the minimum possible effort whereas modern Japanese bikes – even fairly standard models – were on the cutting edge, making 150bhp/litre with total reliability. It’s wild to think of it, but the 2002 Ford Ka was using a 60bhp, 1297cc version of the same Kent OHV engine used in the 1959 Ford Anglia my Dad learned to spanner on. Even Harley wasn’t trying to flog a 1950s engine in the 21st century.

In recent years though, things have swapped around a little. Car engines are now much higher tech – partly because they have to be to meet emissions regs. They’re now crammed with high-powered computers and sensors to analyse combustion and exhaust processes, while turbochargers are common to help cleaner, smaller capacity engines make the power needed to drive increasingly lardy SUVs around. Variable valve timing, direct fuel injection, lightweight all-aluminium construction, they’ve got the lot, and even a fairly standard family car now makes over 140bhp/litre.

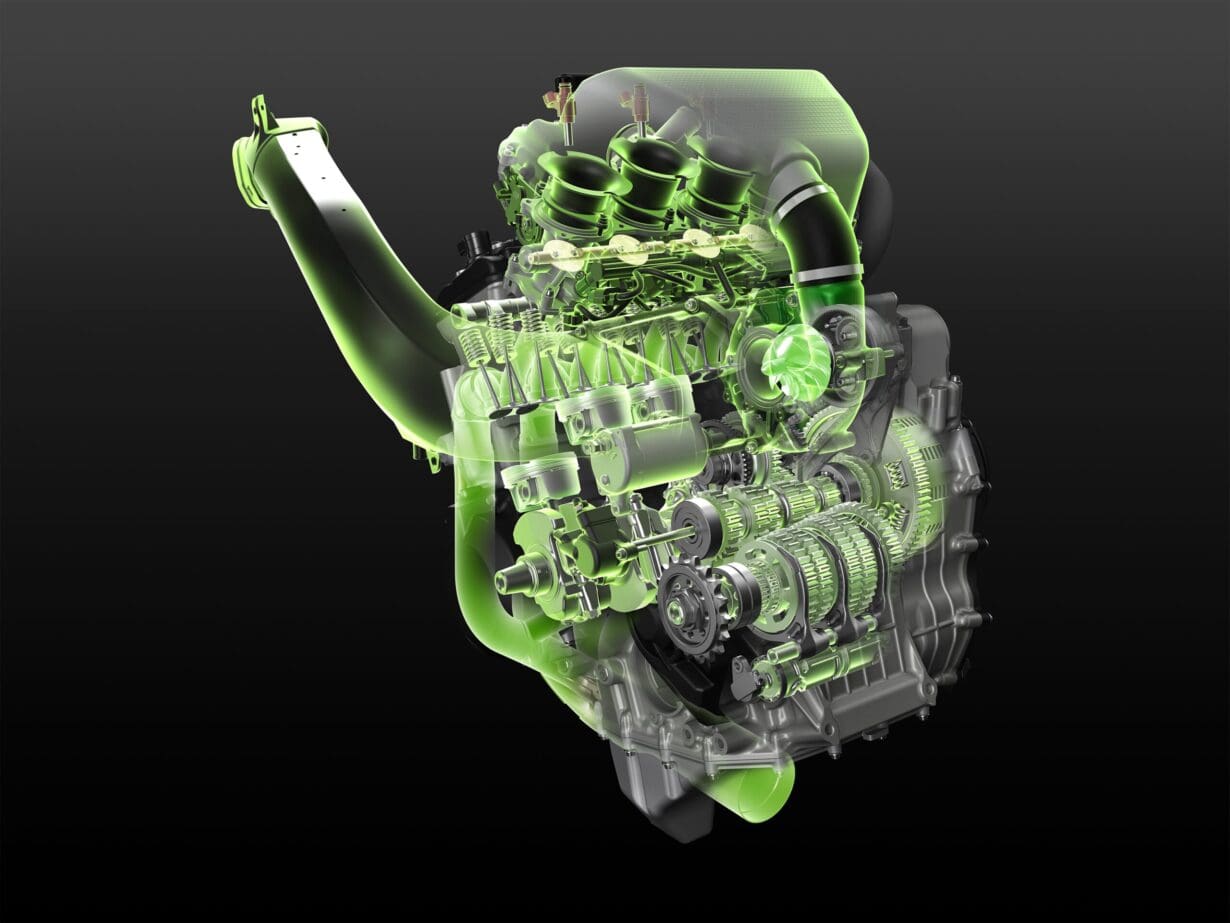

By comparison, bike engine tech arguably has stagnated a little. There are exceptions: the Kawasaki H2 has added a compact engine-driven supercharger (though development there seems to have stalled), while the litre-class superbikes are making 215bhp/litre with natural aspiration, which is an incredible achievement. Things like the BMW Boxer unit powering the new R1300 GS are fabulous designs, making great power with the ShiftCam variable valve set up. Ducati’s desmodromic valve actuation is still unique, giving it a particular advantage. And there have been impressive advances in electronic riding aids, coupled with ever-smarter ride-by-wire fuel injection and engine management.

But fundamentally, bike engine design has stood still, or even retrenched, with cheaper, less powerful parallel twin engines now dominating several important areas of the market. They’re great powerplants in their own way, of course, but they’re not doing much to drive forwards technology in the way that car engine design has been doing of late. If you took a 2024 Honda CBR1000RR Fireblade engine back 40 years to 1984, the performance would blow the mind of any engineer who looked at it. But they would take the design as read: there’s nothing weird about it when compared with a contemporary machine like the CB900 or VF750: four valves per cylinder; twin overhead chain-drive cams; plain-bearing crankshaft; light aluminium pistons; aluminium crankcases; wet clutch; sequential dog gearbox; chain final drive…

The reasons are manifold, but the gradual decline in the European ‘big’ bike market has to play a part, while the high-performance bike market has declined even more, for reasons we all know: an aging demographic, with less interest in sportsbikes for use on congested, heavily policed roads high up on the list. Bikes have had to meet emissions regs, too, in the past 20 years, and have tended to do so with less innovative methods. Indeed, firms are starting to give up. Yamaha’s R1 and R6 have been discontinued because the firm doesn’t want to spend the money needed to pass tighter regs. The engines in the replacement R9 and R7 are much less powerful, but cleaner and cheaper designs.

My Dad passed away a few years ago, and while he mostly gave up working on cars as he got older, he still knew what was what. He was always amazed by the tech in the bikes I visited on over the past 20 or 30 years – and even more so by the power they made. And in a pleasingly symmetrical twist, the computer skills that he gained from working for IBM would now transfer nicely back into the car and bike world where he began…