Last month we gave a splash to Elspeth Beard’s new book Lone Rider, and here’s another publication from a female overlander – Jacqui Furneaux. Of course, there are differences. Elspeth was 22 when she set off around the world on her BMWR60, with a definite plan of where she was going. Jacqui was 50, and as her book’s subtitle points out, had no plan at all.

Last month we gave a splash to Elspeth Beard’s new book Lone Rider, and here’s another publication from a female overlander – Jacqui Furneaux. Of course, there are differences. Elspeth was 22 when she set off around the world on her BMWR60, with a definite plan of where she was going. Jacqui was 50, and as her book’s subtitle points out, had no plan at all.

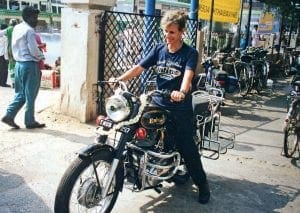

At an age where many people are worrying about pension plans, mortality and younger, faster moving colleagues, she took a five-year break from her job as a health visitor, flew to India and bought herself a new Enfield Bullet to celebrate her 50th birthday.

The plan, such as it was, involved travelling a while with Hendrikus, a fellow overlander, also on an Enfield. She had had bikes before, but the Bullet and its intensive maintenance requirements was a steep learning curve, especially after Hendrikus went his own way in Australia and Jacqui was left to her own devices. But she learnt how to do that, and a lot of the book is about how she overcomes her fears and learns to love solo travel, which includes looking after the Enfield.

Enjoy everything MSL by reading the monthly magazine, Subscribe here.

Jacqui Furneaux is an honest writer, describing many of the downs of travelling as well as the ups, but what really comes across is her sheer delight at being out on the road, seeing the world and often camping next to her bike. “To my delight we went off-road,” she writes about riding through India, “and slept outside by rivers and in orchards. Twice my bike fell on me during the night, soaking me in petrol as I slept beside it in mango groves with soft ground, so I tied it to a tree like a rancher securing a horse at a corral. In the hills of the Eastern Ghats we slept on a huge, flat rock overlooking the vast plain below. Because the rock held the day’s heat all night, we didn’t need bedding.”

Of course, there are scary moments, two of them funnily enough on boats. Jacqui had to ship herself and the Enfield from Malaysia to Australia, and was offered a ‘work your passage’ ride on a decrepit catamaran. Short of water, attacked by pirates and fending off a lecherous skipper, she jumped ship in Indonesia. Then, on a yacht, which promised to bypass the Darien Gap, there were collisions, complete electrical failure and an attempt by the boat owner to use the Enfield as an anchor.

The trip with no plan turned into a seven-year safari, Jacqui and the Enfield riding across Australia, New Zealand and South America before turning north and heading for home through the USA. Book reviewers like to concentrate on the exciting, scary bits (see above) but the overwhelming impression is how helpful and friendly most people were – when things went wrong, with the help of complete strangers, they always worked out.

The trip with no plan turned into a seven-year safari, Jacqui and the Enfield riding across Australia, New Zealand and South America before turning north and heading for home through the USA. Book reviewers like to concentrate on the exciting, scary bits (see above) but the overwhelming impression is how helpful and friendly most people were – when things went wrong, with the help of complete strangers, they always worked out.

Like Elspeth Beard, Jacqui found easing herself back into home life far more difficult than she expected, but this book has a bouncy, optimistic feel to it, which makes one thing clear – it was all worthwhile.