Himalayan passes by Enfield Bullet – landslides, altitude sickness and not a lot of road.

This ride was the hardest, most fantastic and rewarding thing I have ever done. Twenty-one riders on 16 bikes left Vashisht, a hill village in Himachal Pradesh, north India. There were three couples (I admired the pillion wives for their bravery and endurance), two pairs of younger lads who shared the riding, three solos in their Thirties from Singapore, and me, the token white guy. We had two mechanic/ relief drivers (both named Sonny, conveniently), a driver named Lucky and Gaurav, our road captain.

Our destination was Srinagar, which is roughly 1100 miles by rough mountain road (there is only one) but it seemed more like 2000, measured in pure joy, adrenalin-fuelled exhilaration, courage and emotional turbulence as rugged and vast as the majestic Himalayas. I discovered more riding skills in the first few days than I had in 10 years riding on ordinary roads, and I loved every minute of it.

They started us off with a 45-mile round trip into the pine forest hills on what was evidently an evaluation. This is where I discovered that changing the line halfway through a stretch of deep mud with submerged rocks is not a good plan! To avoid total plonker disgrace I decided to put a foot down and stop, but then I needed a push, though I did manage to complete the ridiculous obstacle course. But it was hotter than expected, and having followed instructions and togged up with thermal undies and thick shirt, I very nearly threw myself into the waterfall where we stopped for lunch. The tough riding meant some were considering packing their bags already. Still, none did, and the team gelled.

Enjoy everything MSL by reading the monthly magazine, Subscribe here.

A typical day was up at 6.30am, wash, pack, suit up, deliver luggage to support vehicle, breakfast 7.30am and be on the bike at or soon after 8am, tank bag loaded with mineral water, camera and snacks. Gaurav would brief us on the ride ahead: the distance, special features to look for — water crossings, steep gradients. Then we’d leave, initially in convoy, with instructions to re-group, usually at a tea dhaba, temporary makeshift cafes that are often run by families who live up here in the mountains from April to October, returning to valley villages for winter. They’re often used as army checkpoints as well, the road being maintained by the military.

This system worked well. It could mean riding for 20 miles or more on your own, and I often ambled along at an easy 25mph, the engine’s distinctive exhaust note bouncing off the bare rocks alongside. You might also be in a small group of riders, but I was always able to ride at my own pace. And there was no chance of the last rider getting left behind, as the support vehicle acted as sweeper. Not too fast, not too slow; Shanti, Shanti.

DODGING THE TRUCKS

The rules of the road are made up on the spot in these situations, but everyone was aware, anticipating, which was just as well. Once I found myself on the ‘wrong’ side, following a line, before being aware of the lorry bearing down on me, giving himself all the turning space he could to negotiate the tight, steep right-hander. He was hard up against the cliff, cutting off my road. With telepathic aplomb he braked just enough so not to slide, allowing me to across the front within inches of his bonnet, but safely, both of us doing 10mph.

Changing line on two wheels in these conditions is normally a no-no, but needs must, and forward momentum took precedence over stopping, waiting and falling off. A tap on the horn completed a thank you and complicit understanding – while we all shared this extraordinary road, helping each other to get to the end of each day in safety.

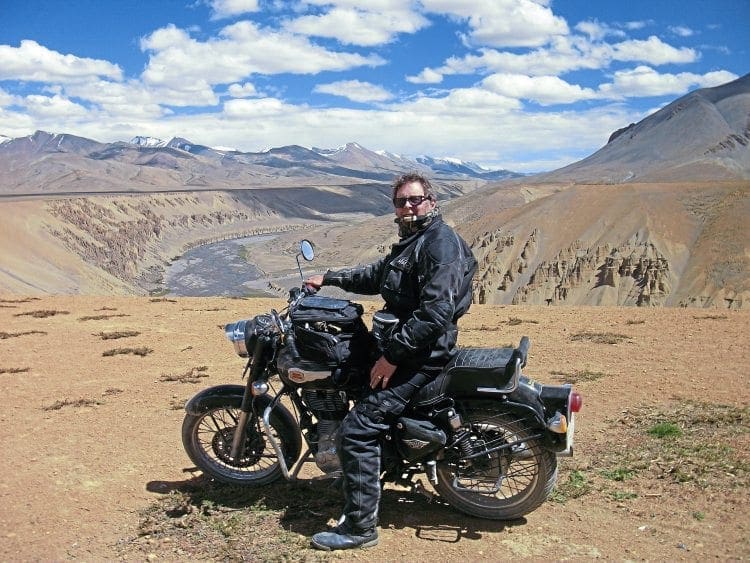

It was all about co-ordination, timing, control, emotion and physics, fuelled by a constant sense of euphoria. I was in the Himalayas, probably the most spectacular mountains in the world, the sky was deep blue, the air crystal dear with no pollution; it’s was a comfortable 20°C and I had a lovely Enfield Bullet underneath me.

Ginger lemon honey tea became a favourite, and it is reputed to help combat altitude sickness. Starting at around 800m, we were soon hitting 4000, seemingly summed up by breathlessness, light-headedness, nosebleeds, a slight loss in appetite and constant thirst. But none of the dragging headaches I had falsely anticipated, and a course of Diamox tablets taken for the first four days probably helped there. There was no such drug for the Bullet engine – they were older carburettor bikes and they struggled to breathe, losing power, the air filters blocked. Otherwise I couldn’t fault them.

By day three we were over the Rohtang Pass (nearly 4000m) and we’d been warned it would be cold, but I was melting in my quilted linings, fleece and neck scarf. Here’s what I wrote in my diary:

‘What a fantastic, stonking, crazy ride today. Enjoyed it all despite the extreme road conditions, jostling with lorries, other eclectic traffic. Amazed at how busy the ‘road’ is. But it is the main road, I keep forgetting, constantly being re-made, the mountains effectively falling down the whole time. We battle with loose gravel, deep dust like talcum powder sand. Roasting hot, relentless concentration, tugging on bars, hammering ride but somehow I’m coping.

‘Stopped at dhaba after the Pass for chat. Rustic is a kind description! But clean, mountain air, water straight out of the ground, not ally in sight. We are still in India, officially, but not the India many would recognise.

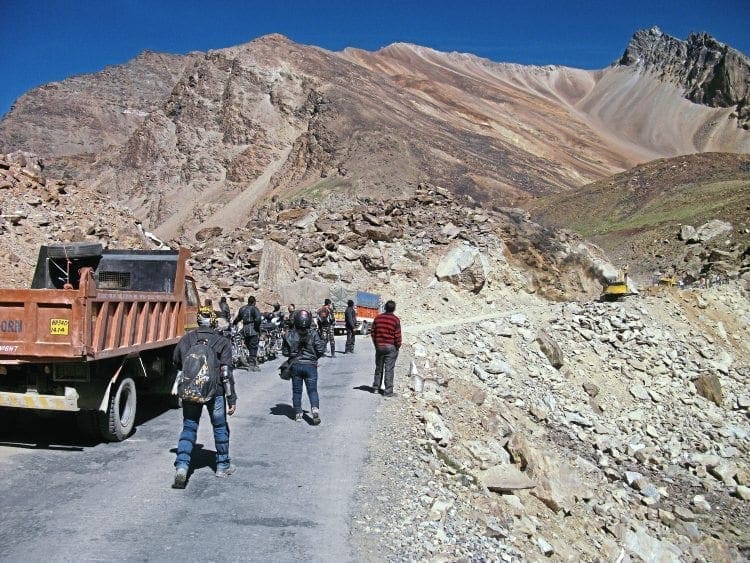

‘Soon after lunch an extended water obstacle, the river flowing along the road, not deep, but foot wetting with plenty of washed-out gravel means I cheekily follow another bike, watching for the bad holes. This few hundred metres leads to a rare bit of Tarmac road surviving last winter’s freeze. But it then deteriorates, ending in a massive landslide, completely blocking a narrow curve. A Hymac and huge bulldozer belching black smoke grind and screech clearing a way through. Within 20 minutes there is room for the bikes to get past.’

Initially, the sheer magnitude of the mountains, the unaccustomed road conditions and the concentration on bike control consumed all my awareness. But as I settled into a rhythm, I left behind those fears and inhibitions. I left behind a known world, and to some extent, a person (me). Suddenly I realised I was in my element, doing this incredible thing, expanding into the excitement, not intimidated, but relishing it.

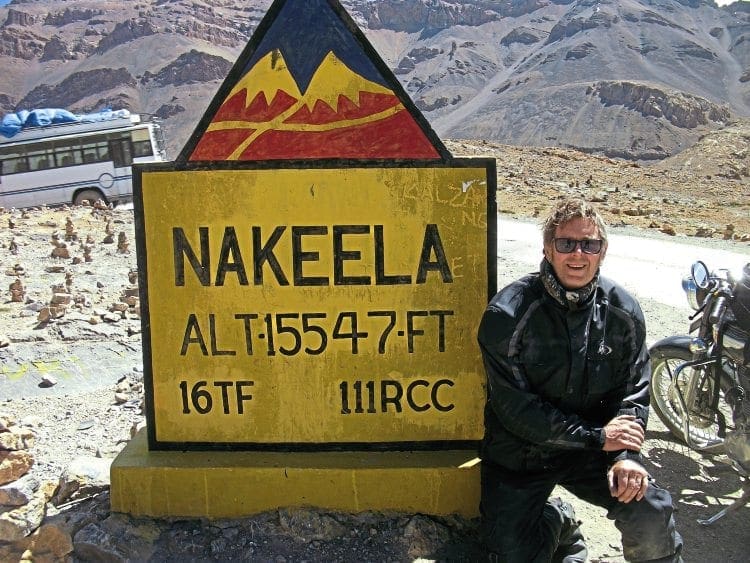

The high passes are all denoted with hundreds of Buddhist prayer flags. These colourful message carriers flutter endlessly, about the only animated things up here in the stony wilderness, sending positive thoughts into the ether. The highlight among many was Khardung La pass (5400m). We were all acclimatised by then, but we were still advised to stay at the top for no longer than 20 minutes. Most of us lingered longer, perhaps risking a few grey cells, but it was worth it!

Next day, after the visit to Hunder sand dunes and Diskit Monastery, we rode back over Khardung La pass, another bone-hammering, bike-shaking 20 miles. Teams of women were breaking stones and fitting them together like a giant jigsaw across the road. I left the top, not wanting to hang about, and followed Dan down, but I lost him after a few miles. Then I got lost in Leh, unable to find the hotel, retraced my route with the idea of meeting the support plan. But my brain was very sluggish after a long day, my right foot slipped on loose gravel and down I went. I stood there, looking at my lovely bike lying on the road. Fortunately, I was able to lift it upright before any of the guys turned up.

TT ENDING

It wasn’t all dust and high passes. Pangong Lake, a salt-water phenomenon at 4350 metres, over 60 miles long and three miles across at its widest, is 40% in India and 60% in Tibet. The Tibetan name is Bangong Cuo – long narrow enchanted lake. It was still cold at that altitude, but our wooden huts and Tibetan quilts kept us cosy, as did the excellent rice, dal, veg and egg curry, with lashings, you guessed, of ginger lemon tea. Some opted to sample the freeze dried vacuum packed chicken rations bought on the cheap from the local army base because it was a tad out of date!

Extract from diary, day 12:

‘Route Kargil-Drass-Zoji la Pass (3528m) Sonmarg-Srinagar – 200km. A long day’s ride with bad patches of road. The road after Drass is rough. Zoji la Pass is famous for its slippery slush, so ride with caution in low gear. Entry from the highway to Dal Lake Boulevard in Srinagar has heavy traffic and many turns. We ride in close formation. Party at the house boat.’

The highway turned out to be a dream. To end the ride we had a perfect six miles of beautiful new road. It was like TT racing practise, getting the knee down (on a Bullet? Ed) on the sweeping corners until the tyres just began to creep, another exhilarating episode in a plethora of extremes. The whole journey had been one of exquisite sensory overload, and it was with a mix of nervous exhaustion, gratitude and surprise that we all arrived safely at our journey’s end.

The organisation was just right. We had the freedom to experience the ride and enjoy our new group of friends without all the headachy logistics of where to stay, petrol, breakdowns and permits. All that was taken care of and we ended each day pumped up with exhilaration, dusty and knackered, but confident there were a hot shower, dinner and a comfy bed waiting. Even the two glamping nights delivered.

There were just three minor accidents. Two of the younger riders left the road on a corner, fortunately not disappearing over a 1000ft drop, but just 10ft, though still enough to scare the chai out of one lad, who refused to ride for two days. Next was a skid on sand into the front of a jeep – bent crash bar, dented tank, no injuries. Finally, another soft surface skid and tumble, which meant bruised ribs that needed X-raying that night in Leh, in case they were broken. This guy had broken his ribs and collar bone just three months before, so he sat out the last two days riding.

Still, we all survived, and Gaurav emailed us all afterwards: “You never completely come back from Ride of My Life,” and I now know what he means.

WORDS & PHOTOGRAPHY: Alistair Matheson

[googlemaps https://www.google.com/maps/d/embed?mid=1gT402xJPjJl6q-UrVGdbiybdyIA&w=640&h=480]