Paul Smith rides through Belgium and France to find the grave of his great uncle, who died on the Somme

Wouldn’t it be great if there was a country about twice as big as the UK but with no more people, well-maintained roads, where bikers were generally welcomed and respected, and that could offer world-class food and other attractions to suit all tastes and budgets? Well, it’s real, it’s called France, and it’s a great place to tour on bikes of all sizes. With multiple ferry routes as well as the Channel Tunnel, there are lots of choices of how best to get there. And it’s all too easy to miss out on the delights of the north in your hurry to get somewhere else!

My trip was specifically to locate three family war graves and photograph them for older members of the clan who are not able to travel. At the same time, I wanted to meet up with friends I hadn’t seen for 38 years, eat some great food and see some impressive and moving sites.

Living in Derbyshire, I opted for the Hull-Zeebrugge night crossing, which was quite dear at £350 return, but that did include sole use of a cabin (with a window), breakfast and for me it had the big benefit of cutting out a long ride down to, and back from the Channel ports.

Enjoy everything MSL by reading the monthly magazine, Subscribe here.

Heading south out of Zeebrugge on the Friday, I was immediately struck by the straight open roads, and on the first day I located the first of the graves (that of my nan’s first husband) and visited Ypres with its moving ‘In Flanders Fields’ museum. Also the Menin Gate where to this day, the Last Post is played in a simple remembrance ceremony every night.

From a language point of view, it certainly helps in France if you can manage a few words of the language, but in Belgium (especially the Flemish-speaking north, for example in and around Ypres) you’ll actually get a better response by speaking English, even though the town is just a few miles from the French border.

CLOSE QUARTERS

On the Sunday, I headed down the Paris autoroute to Péronne on the Somme, and Lapugnoy near Béthune to see the other two family war graves. These cemeteries are moving: their design gives them a very British feel and the thing that strikes the visitor is not vast fields of headstones, but just how many of these graveyards there are. It’s easy to see that every slight bump in the landscape was fought over again and again, changing hands many times during the conflict.

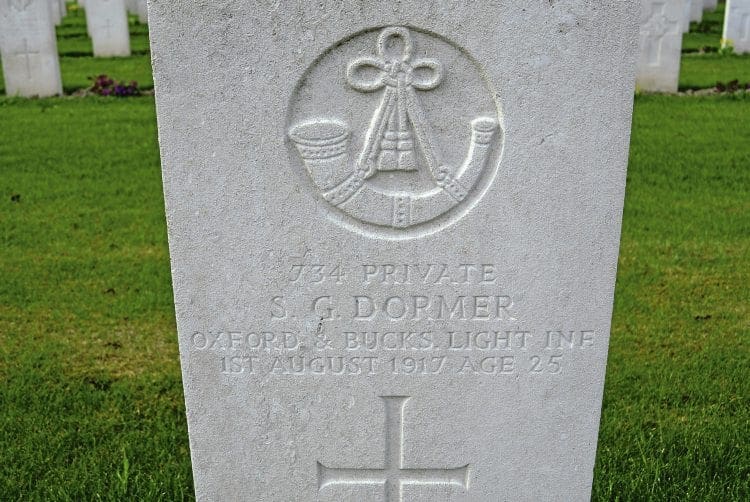

Tracing the graves is easy thanks to the meticulous records of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (www.cwgc.org) but finding out more about what happened to those who were killed is much harder, not least because of the sheer numbers involved. Of the three family members whose graves I visited, I know most about my great uncle Sergeant Edwin Smith. Born in 1892, he died on April 28, 1917, (aged 26) while serving with the Notts and Derbyshire Regiment (Sherwood Foresters).

His battalion was sent to Ireland in April 1916 to quell the Easter Uprising before being moved to France, landing at Boulogne on January 12, 1917, in order to join the fight on the Somme. The official announcement of his Military Medal doesn’t appear until the London Gazette published on May 26, 1917, so it looks as if it was awarded posthumously for whatever action he was last involved in. I know he died of his wounds at the 33rd Clearing Station one mile south of Péronne (at the southern end of the Somme front line). Since he’s buried at La Chapelette, itself one mile south of Péronne, it seems he was buried very close to where he died. He’s just one of the 1.5 million who were killed, injured or who just disappeared during the Somme fighting.

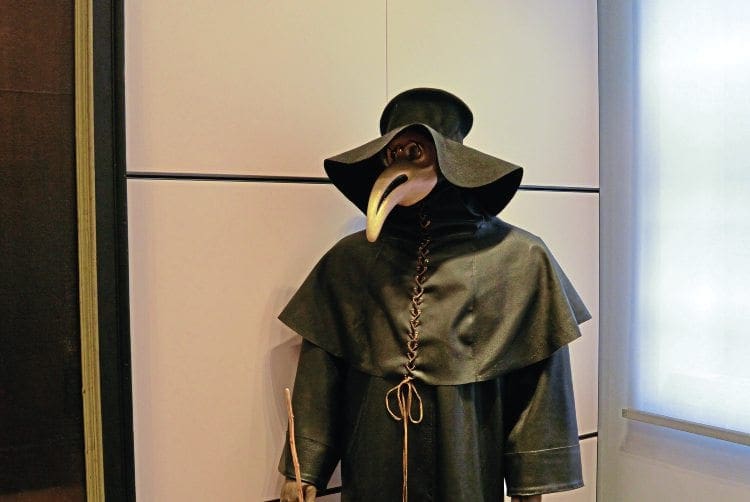

Sometimes when travelling, the most memorable things are those you find by chance. That’s what happened for me. One was the convent of Notre Dame de la Rose in Lessines in Belgium – an amazing and almost unchanged convent-based hospital complete with medical books, surgical instruments and therapeutic herb garden.

Even more moving was the museum and cemetery at Fromelles, about 15 miles to the south east of Lille. Here the Germans buried many Australian war dead in mass graves, but in 2009 a decision was made to exhume the remains and use modern forensic and DNA technology to identify them. As a result, many have been given a final resting place with their name on a headstone instead of the anonymous ‘a soldier known only to God. It’s easy to see from the numerous messages and planted Australian flags how much this has meant to surviving relatives who’ve come from the other side of the globe to honour their dead.

If there’s one thing I would have changed about this trip, if I could, it was the weather. Every day I was riding we had hail at some time, and it was always cold and wet. On the plus side, the bike (eight-year-old BMW F650 GS) always started first time, handled as well loaded as unloaded and never averaged less than 70mpg, giving a 200+ mile range to a tankful.

Among the French, Belgians have a poor reputation when it comes to driving, but I saw little difference, either between those two nations or by comparison with drivers in the UK. I’d say that, in both countries, people will respect you if you ride purposefully, predictably and decisively but that’s probably true anywhere. The area provides a huge range of roads, from motorways through to tiny roads between villages: each brings a different pace and rhythm.

That said, road surfaces were usually good (better than the UK average) and signage clear. And even though Lille is a metropolis of more than a million people, it’s not hard to find, on its outskirts, near deserted roads – if peace and quiet is what you want.

Advice for France & Belgium

- Taxes in Belgium are lower than in France, so if touring near the border, fill up with fuel, fags and booze on the Belgian side to get the lowest prices. Also, there’s no peage (toll) on Belgian motorways, but it’s the norm in France. Carry enough euros to pay your toll in cash, just in case your debit card is refused (as happened to me).

- Don’t forget to wave at other bikers (motards): the convention is to extend the left hand with the palm open: as you’re riding on the right, that’s the nearest hand to riders coming in the other direction anyway. Bike-riding Gendarmes (police) won’t acknowledge you unless you’re misbehaving.

- Beware of the strict ‘priorité á droite’ rule, which still applies in many built up areas of both France and Belgium and can lead to a fright when people to your right pull out in front of you, quite lawfully. Put red electrical tape on your right hand mirror stalk if you need reminding of the ‘give way’ side.

- Plan your journey back to the ferry/tunnel to allow some slack: you don’t want to have to race to catch your crossing!

- It’s worth noting down the location of a main dealer for your make of bike near where you’re going, in case you need spares or assistance.

- Don’t forget your documents: in France you must carry your essential paperwork (registration, insurance, MoT plus proof of identity). Don’t forget spare keys – and glasses too if you wear them!

- Set up your sat-nav carefully. I couldn’t understand why I was being routed along tiny farm tracks (not always paved) until I found my device was set to ‘shortest route’ rather than ‘quickest route’.

- You can’t be too visible: I ride with headlight on and in light-coloured clothing; I’ve also always fitted extra lights to my bikes. With 12V LEDs available so cheaply, this is a really low-cost mod to make and I’m convinced it’s a lifesaver.

Words & photography: Paul Smith

[googlemaps https://www.google.com/maps/d/embed?mid=1wRialOX0GMRsf-ZUHv6GBw69QeY&hl=en&w=640&h=480]