TESTED BY: John Milbank¦£419.99¦www.nevis.uk.com¦01425 478936

My perfect leather jacket has to be understated in its design, and given that I love street bikes, I want a fairly retro style, but with a good level of modern protection. It’s got to be comfortable too, both on and off the bike, and it mustn’t scream ‘I’m a bike jacket’. This Furygan does all of that, and while it’s not cheap, I’m expecting it to last me very well, despite things not going quite according to plan at first…

The Legend is CE approved to the French protocol, which is not as stringent as the general CE Level One and Two standards we’ve become used to, but a format agreed by the French government to help introduce tighter regulations on the gear riders wear. The soft leather feels superb, and is triple-stitched in high-risk areas, with slim D30 Level One armout at the elbows and shoulders, which is great as it adds very little bulk to the jacket. There’s a pocket for a back protector, though sadly one isn’t included – I’ve fitted my £29.99 Furygan Level Two Viper Pro protector, which doesn’t add too much bulk to the back of the jacket, and still feels fine when off the bike.

Enjoy everything MSL by reading the monthly magazine, Subscribe here.

The quilted lining looks fantastic, and feels good, even during my very hot ride to Spain this summer on the XSR700. The collar and cuffs are comfortable, though I’d have liked to have seen an extra popper securing the cuffs, or the inner leather flap reaching right across the zipped opening.

The main zip is a metal YKK, and while the puller feels a little flimsy, I’ve had no problems with it. Along with a zipped inner pocket, there are three on the outside, and it’s here I had a problem. While riding in Spain the right hand pocket’s zip detached from the leather outer – everything was still safe inside, and the zip worked fine, but it would need replacing.

As I’d worn the jacket for a few months by this point, a repair was the best option; usually the shop that sold it would arrange for it to be returned to Furygan’s factory in France, where the repairs department is the same team that builds the custom race suits – like those of Sam Lowes – and uses any warranty claims (not to mention items sent in by long-term customers who simply don’t want to part with their old jackets), as learning tools for product development. So, I thought I’d go with it to find out more…

FROM THE DRAWING BOARD

Every Furygan garment starts in the design department – Nicolas Afanassieff is the man behind the race gloves, suits, rucksacks… and my Legend jacket. “The inspiration came from Furygan’s products of the 70s,” he told me. “The chequered stitching of the shoulders is a tribute to the inner linings of the 70s. I also draw on things I see in magazines, in custom shops, online and in second-hand clothes shops. Today’s custom culture is so unique that there are many influences – you can’t really put it down to a single person or brand.”

Once a design is created, Marie-Sylvie Arnese is one of two women who design the paper pattern template. These have to take into account not just the style, but the economics of factory production. No small task, but of course each item has to be templated for several sizes, or ‘graded’, which is not simply scaling proportionately – “It’s just as difficult to grade each garment as it is to create the first template in large,” she tells me, “which is the most common size and the one that we use when creating prototypes!”

The templating process needs to take into account the extra leather needed for seams – a full centimetre to ensure the triple stitches needed for a safe, secure join, has plenty of space. And when she’s not doing all that, she’s creating the bespoke templates for the 120 or so race suits made every year.

These one-off, but finished quality products are then shown to the global distributors, who decide if they think they will sell well in their markets. Having seen some of the designs that have been turned down, it’s a real shame that not all make it. It’s not all wasted time though, as there’s always something to be learned, and that same item could become a hit a few years down the line.

FROM PAPER TO LEATHER

The leather for Furygan’s jackets, trousers and race suits is bought from an Italian tannery, with most of the cows raised in South America. Only the glove leather is bought from Asia, where goat cattle is far more common, the leather being softer and more suited to gloves. Also, remember that Hindus consider cows to be sacred, so their slaughter is forbidden in much of India.

A cow skin is about one centimetre thick, but different parts of it are used for different goods. A chamois comes from the bottom of the skin, whereas ‘full-grain’ leather is the outside, bearing all the scars and marks of the cow’s life. Besides on some of its vintage jackets, Furygan uses the next layer down – a less textured, but more consistent quality of hide. This causes less wastage, which is important with up to 800 garments cut every week at the small factory, staffed by just 47 people – that’s 100,000 square metres per year, or about 40 football pitches. At the tannery, an additional texture is pressed into this Leather, and it’s what’s used in my Legend jacket, in the one-piece leathers, and some of the sponsored racers’ custom-made suits. Some racers prefer kangaroo hide, though it takes eight kangaroos to make a race suit, as opposed to just one cow.

Each hide, which is on average 1.3-1.4mm thick, is laid out on a table – it takes half a cow’s hide (literally the left or the right side, about 2.24sq m), to make a jacket. As hides vary across their area, the staff mark any areas that are thinner, weaker or damaged with coloured chalk. The differences can be incredibly subtle, so it takes a keen eye to spot every imperfection. Larger portions that are thinner in the hide are cut out and used for making elasticated stretch panels, to help them be as flexible as possible.

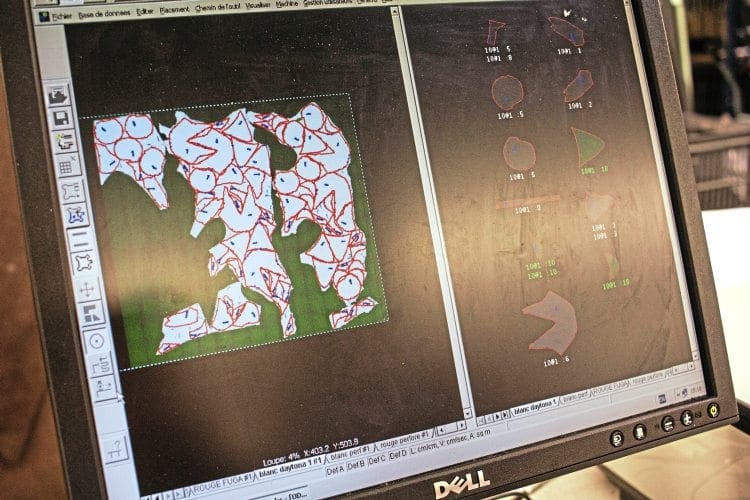

From here, the hide is laid out on the table of the Taurus machine – an arm stretches above the hide and first scans it to work out the size and shape of the leather, as well as recording the position of the chalk marks. Using the digitised templates created by Marie-Sylvie, it then works out the most efficient possible way of cutting the leather, using a frighteningly sharp circular blade that’s replaced every day.

A race suit might need white, white perforated, red, red perforated and black leather hides to all be cut.

Some parts are cut manually using dyes to stamp out from the left-overs. With metal stamps also being used to cut the Furygan logos and other lettering. Racers’ custom-made suits are all cut by hand, using the paper templates as a guide.

With all the parts sorted – 30 for the Legend, or around 150 for a one-piece suit – they’re packed in crates and sent to Furygan’s 80-strong workforce in its own Tunisian factory for stitching. Once complete, everything is returned to the base in Nimes to be individually checked, steam ironed, the D30 armour fitted, tags attached then sent out to the worldwide distributors.

Repairing my pocket took just five minutes, and it’s impossible to see where it was done. Obviously it’s disappointing in something this new, but I’m glad to have what is a stunning jacket back in time for the coming new bike launch season, which sees my kit get a lot of use in all kinds of conditions.

Why Furygan?

The Segura family had been making protective gloves in Nimes since 1963, but in 1969 Jacques Segura wanted to extend the range to include motorcycle gloves. A big fan of bikes, a family dispute led to him leaving the business to start his own company, Furygant – Gant meaning gloves, and Fury representing a ‘furious desire to succeed’. It would have been simply ‘Fury’, but another local company had the name ‘Ferry’. Later, the ‘t’ would be dropped, to become Furygan.

The first sales reps had been cadets with the 11e Choc – the French Army’s elite parachute regiment, whose insignia was a black panther’s head. The panther, showing its claws, became Furygan’s logo, and while the regiment no longer exists, Furygan still produces parachute helmets for the French military.

The family feud persisted, and even right up to his sad passing in September 2016, Jacques Segura was always address using his first name; Monsieur Jacques. The tradition persists with his son David, who now runs the business.

What is D30?

The short answer is that, in its raw state, it’s a non-Newtonian fluid (like corn starch and water), which means that its shear rate is not proportional to the sheer stress, the proportionality being the fluid’s coefficient of viscosity. Got that? Okay… basically, if you strike a non-Newtonian fluid like D30, it will go hard. If you push it slowly it will flow.

Usually seen by the end customer as a polyurethane foam material after being mixed with other secret polymers, it’s great for motorcycle kit as it can be made relatively thin and unobtrusive, especially in the CE Level One products, though Level Two is also available, and particularly popular in back protectors. It also tends to conform to the rider’s shape well, and is very resilient. D30 says that its armour won’t compress and deteriorate, so owners simply need to keep an eye on it for signs of wear.

The technology was developed by British engineer Richard Palmer, and quickly became popular in winter sports, being used in a ski suit in the 2006 Winter Olympics. There are over 25 different types of D30, covering motorcycle products, the construction industry, military and more, and UK-based D30 (Dee-Three-Oh, not Dee-Thirty) can supply the industry with either sheets of the product, or with custom-made items, such as Furygan’s protectors.

Rumour has it at the company’s headquarters that the name comes from Richard’s room number at the University of Herefordshire, though others think that it might be linked to a chemical formula in some way.