Bruce Wilson ride the epic Trans Baviaans Expedition on a Triumph Tiger 800 XCx.

Day one of this incredible expedition, and we were deep in the land the South Africans call the ‘bush’, surrounded by heckling wildlife and without a clue as to where the hell we were. Phone signals had gone long ago, as well as fresh drinking water, electricity and general signs of civilisation. Standing around me were 11 other guys, each as bewildered as myself, each just as awestruck by the towering red stone rocks that enclosed us – and each as eager to claim their night’s tented accommodation and crash out for some much-needed rest. Well, until the warning came to check for scorpions that is.

Until that moment, the prospect of coming face-to-face with one of those nasty little nippers felt about as likely as buying a winning lottery ticket. But things had changed. This was Africa and, as concerning as a coming together with one of those stingers might have been, they were relatively small fry compared to the more sinister animals roaming around our camp. The skin prickled alarmingly at the thought, with the only solution being to light a huge fire, crack open some beers and kick back under the overwhelming display of stars while our South African hosts cooked amazing food on a braai (barbecue)…

It was a time for celebration. For most of the riders in the group, Trailquest’s Trans Baviaans Expedition had been little more than scrawled words on a calendar for well over a year. Were we ready for what awaited? It was impossible to tell, but we each felt as prepared as could be. The training we’d put in with Trailquest in the UK had not only brought us together as a team, but taught us key riding skills that were certain to make our trip that bit easier. Add to that an afternoon exploring South African travel partner I-ride’s Leeuwenkloof (Lion’s Gorge) training grounds, riding the brand new Triumph Tiger 800s we picked up a few hours earlier from a dealership in Johannesburg, and you’ll understand why we were all feeling so confident and excited.

Enjoy everything MSL by reading the monthly magazine, Subscribe here.

Of course, some were more nervous than others. The group was made up of people with very different levels of riding experience and self-confidence. It had been evident earlier in the day when we’d headed deep into the remote 750 acre Leeuwenkloof playground and put our skills to the test across a variety of riding challenges. As comprehensive as our training had been in the UK, there simply hadn’t been the opportunity to test a Tiger through long sections of foot-deep sand, learning how vulnerable the bike would be made to feel as the front end tried relentlessly to bury itself and fold the bars to the side.

There were quite a few crashes during this exercise, but none of those who hit the ground stayed down for long. They were up and running the course soon after, desperate to get the hang of what the South Africans were saying would prove an essential skill during our 2000 mile trek to the other side of this enormous country. Cape Town was our destination, taking eight days of hard riding to reach the end of our trip, with our night’s briefing from I-ride’s boss Andre Visser giving us a good appreciation of what we could expect to be tackling that next day. The crux of it was a long, hard day in the saddle. That was our cue to hit the sack and get some sleep.

THE FIRST PUSH

Day two kicked off with each of us nestled in our tented accommodation, shivering away in the freezing night air. For the majority of the group, that much-desired sleep had proved hard to find, and a chorus of exotic sounding wildlife from 4am onwards meant we were all a little nervy by the time our 6am alarms started ringing.

Still, at least no one had come to blows with any scorpions. It was set to be a huge day, with no fewer than 600 kilometres of road and trail waiting for us. The plan was to get the bikes moving by 7am, but not until we’d devoured our breakfast and warmed up nicely under the morning sun. In the course of an hour the temperature had climbed by 20°C, meaning the under-layers I’d put on first thing were being desperately removed moments before the group was scheduled to head back down the trail that had led us to Leeuwenkloof.

It was a really exciting time as our staggered formation eventually met a Tarmac road and arrived at a fuel station for a top-up. Petrol was cheap; a full tank costing the equivalent of around £7.

The other essential we all took was water. Hydration was to be key to our journey, often meaning that every stop was considered an opportunity to down a pint of the stuff – I made a habit of always carrying two bottles under the Tiger’s pillion seat. In fairness, that level of preparation on day one was overkill; the routes we were riding were mostly well surfaced, taking us through relatively well populated areas.

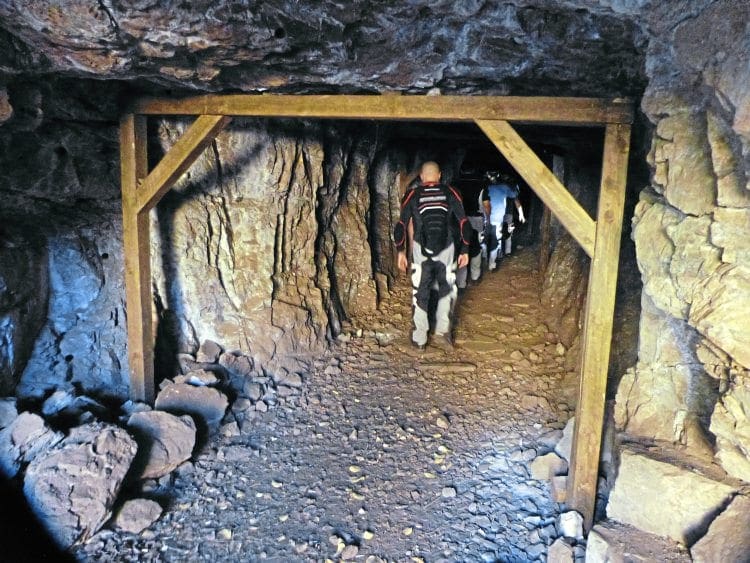

The region was called Gauteng and it was best known for its gold mining and subsequent claim to bringing in around 40% of South Africa’s wealth. Johannesburg and Pretoria lay within its boundaries, along with many endless roads, each surrounded by rolling grasslands. That was the kind of view we experienced from the start, our ride being occasionally brightened by the sight of a roadside baboon or some penned-in antelopes. And then there were the mines; they were enormous and everywhere. The discovery of precious metals and gems had been a real magnet for early settlers in the 1700s, who’d moved hundreds of miles by foot, horse or cart to reach this distant land.

Travelling at 100kph (60mph), the group got into a habit of stopping every hour for a stretch. Service stations were our normal choice of rest area, always taking the opportunity to fill up while we were at it and re-arm with water. Another commodity that quickly became very popular was lip balm, or ‘lip ice’ as it’s known in South Africa. The dry air was a nightmare to contend with, splitting lips and filling your tacky mouth with blood – there’s a lot to be said for mild English summers!

Several hours into the ride we reached a town called Parys, which has two major claims to fame: the site of a 32km-wide crater from a meteorite hit, and the Vaal river which marks the border of the Free State. It was here that we picked up our first dirt road. I’ve ridden a few before over the years, but this one was a particular beast, with several inches of deep sand littering the best part of the track’s width. You either had to be right at the front, or give the rider ahead some serious space if you wanted to stay out of the billowing dust clouds robbing you of your vision and leaving a bitter taste as your teeth ground on the aerated dirt particles. Still, it was a lot of fun and offered a complete contrast to the mundane, endless stint of Tarmac carriageway that had brought us to the trail.

I say ‘trail’ but this was actually a registered ‘regional’ road, which was graded and maintained like any other part of the country’s transport network. That meant we were not on our own, often coming head-to-head with traffic travelling in the opposite direction. You’d first see a huge plume of dirt, which eventually showed a car or truck nestled within it. We’d been told to ride in the tyre tracks left by such vehicles, as the sand had been mostly dispersed from these areas, but if you were in the centre or far side of the road, that obviously meant you had to move to the inside lane’s track. Sounds simple, but to get there meant crossing through the thick-piled sand, which would send our Triumphs weaving and leave us fighting for control.

On one occasion I found myself in such a situation, with my bike’s front wheel frantically slapping from side-to-side as if possessed by the sand. It went on for 20m or more before control was regained. That story ended well, but the same can’t be said for one of our South African guides, who crashed heavily on the route, breaking his ankle, ribs and collarbone. Scarily, no one knew he was missing until we were forced to stop for an ostrich running in line with our formation for well over a mile. We each knew that crashes were likely, but no one could have guessed one of our guides was to be the trip’s first victim. It threw an air of caution over the group, and the return of Tarmac brought some relief to all, including the South Africans who said they’d never known a route in such bad condition.

The wind by this stage was horrendously strong, prompting hundred feet whirlwinds to appear on the horizon. They were everywhere and often coloured by the soil fields that they towered over. The locals didn’t seem too bothered by them, but I thought twice about riding through one as it crossed the road immediately ahead of me. I’d never known wind like it, causing us to ride at an angle to keep straight. Our speed was slowed for our own safety, putting us even further behind schedule. The intended route to Heilbron was meant to have been along dirt roads, but sticking to Tarmac offered the best chance of winning back some time.

The afternoon saw the wind die down and the rolling plains morphed gradually to a more rocky consistency. We were headed towards Lesotho, the mountain kingdom, the skyline littered with towering peaks colouring the horizon brown. We were back on a dead-straight road once more, but that suited us for rubber-necking at the view that seemed to improve with every metre.

For the brunt of the afternoon we’d been travelling on roads that, aside from the odd garage, really had little in the way of civilisation, so when we suddenly arrived in a town it made the day that little bit more special, giving us a chance to speak to locals and take in a bit of their culture. At the centre was a church, and next to that was the only shop. It was a bizarre place, styled from the 1950s and offering everything from butchered meats to antiques. The lady behind the counter was so glad to see us, and explained that no one ever travels her way. Even the local policeman commented on how nice it was to have visitors.

It put our location in perspective; we were miles from anywhere or anything. Growing up in the UK, it’s hard to grasp the vastness of South Africa, with this particular area bearing numerous similarities to riding in the American Midwest. This was the place that time had forgotten.

With the day in its closing stages, the golden sun set over the rocky formations surrounding us. It was a majestic sight, but with the onset of dusk came the terror of night. Most of us were wearing dark visors and that made life pretty difficult when we branched off onto our final trail of the day. We had 15km to cover on the dirt, which strained our eyes to the maximum to see the route’s potholes and built-up piles of sand. The option was to ride near-sightless with the dark visors down, or risk being blinded by the dust storms being kicked up by the riders in front. I chose the former and slotted in as close as possible to our support vehicle, using its lights to guide me to our overnight destination. The relief was obvious on everyone’s faces when we arrived at our lodges. It had been 13 long, long hours…

DAY THREE: LUCKY ESCAPE

Our morning’s first ride took us back down the dirt roads we’d ridden the night before. The trail didn’t seem half as daunting in the daylight, which is probably why I got a bit cocky and gassed my bike into a 70mph tank slapper. I felt the fear in my gut as the Tiger 800 shook its head wildly, leaving me clinging on hopelessly. I got lucky that time, but took note of the warning. Although we had 500 kilometres to travel, we weren’t in a manic rush so there was no need to ride crazily. The crash from the day before had been a constant topic of conversation, with the South Africans admitting that good hospitals were few and far between. There was no NHS out here, just a handful of Toyota minivans you’d occasionally see darting around on the roads. I guess there was an air of vulnerability, which was ironic considering we hadn’t ventured into the remote parts of the expedition by this point. We had all that to come, as today’s ride was a relatively straightforward 500km shimmy south.

By this stage the whole group had become proficient at riding together in a staggered formation. In total, there were 14 motorcycles in our pack, which could stretch out over half a mile at times. Behind the tail rider were two support vehicles that were there to make sure no one got left behind or was left stranded by a breakdown. Up front was Triumph South Africa’s brand manager Arnold Olivier. He was our guide and was a good pace-setter.

The first stop was a visit to a township. In Brazil they’re called favelas and in India they’re known as shanty towns. Made from corrugated steel or whatever wood was available, it was sobering to think about people living out their lives in these primitive homes. Most of us take for granted all that we have around us: our clothes; our food; our bedding; our luxurious motorcycles. But there was none of that here. It was life as I’d never known it, and it made me appreciate what we have all the more.

In the heart of the township was an iron-barred shop. The man behind the counter sold me four big bags of sweets for less than a pound. Richard Jeynes, Dean Miles and I headed a few streets away where we’d seen some kids playing during our ride in. Their screams of joy said it all when we started handing out the goodies; smiles as wide as you’ve ever seen. It was hard to hold back the emotions and equally as hard to leave these amazing people.

We had loads more straight road to cover that morning, riding through endless miles of green fields. The Lesotho mountains had vanished from view, with rolling plains being the wallpaper once again. There wasn’t much to think about other than the comfort of the Tiger, which impressed me more and more. For my 5ft 9in frame, I was well sheltered by the bike’s big screen and loved the plentiful leg space. The bars were comfortably placed and I was drawn to the Tiger’s cruise control function, which often needed moderating to slow down or speed up as the group’s pace meandered unpredictably.

Around midday we made it to Blomfontein. We’d only been on the road for two days, but already it seemed a long time since we’d seen big shops and tall buildings; our dusty riding kit backed up the story. It was nice to see familiar retail names and stare into dealership showrooms, if only for the sake of reminding ourselves of the lives we had back home. This place felt every bit as normal as a trip to the local high street, prompting a feeling of excitement once we started heading out of town. We hadn’t travelled to the other side of the world for normal; we wanted adventure. That was the promise of this trip, and we were easing towards it with every kilometre. As we acclimatised to the host nation and our confidence grew, there was an ever-increasing desire to reach that first big riding challenge and see how we could cut it. But there were still plenty more straight roads…

Having had lunch on a game park, the afternoon saw us riding smaller, winding roads to the site of a Boer war concentration camp. Around the turn of the 20th century the Second Boer War was in full swing, as the British fought the Boer (farmers) for supremacy. Outnumbered, the Boer used their local knowledge to outwit and outmanoeuvre the invading forces with devastating effect. The British retort was to gather up women and children and relocate them to camps around South Africa, in the hope that the Boer men would surrender in order to be reunited with their loved ones. That plan didn’t quite work out, if anything fuelling the fight. One such camp was Norvalspont, which was where we visited. It had seen the internment of nearly 5000 people over the three years it functioned, with nearly 2000 of them dying in the process; most from the spread of diseases such as measles. Walking around the camp was chilling. There was a memorial with so many names on it and it was impossible not to feel shame, despite knowing I’d had nothing to do with the camp’s existence.

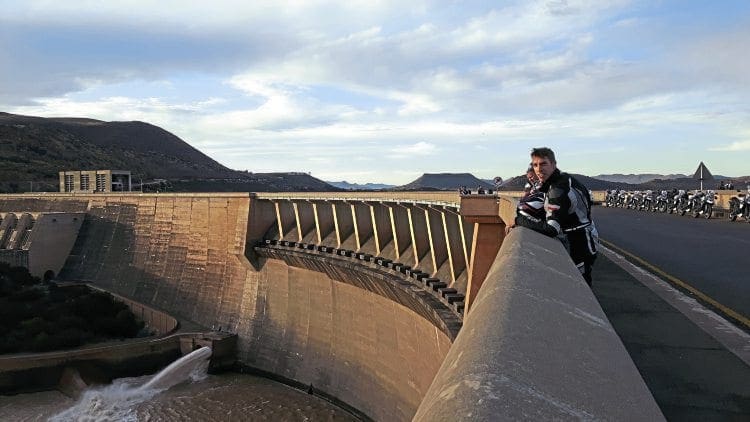

I’ll admit to having been glad to leave the area, with the vast Orange River being a more welcoming view as we made our way upstream towards the Gariep Dam. We rode right on top of the superstructure, which penned in trillions of gallons of fresh water, looking out to the setting sun that lit the surrounding mountains. The original plan had been to ride over the largest bridge in the southern hemisphere, but time had robbed us of that experience. Instead, we rode straight to a Victorian town called Colesburg where we were to stop for the night. It suited me; I was exhausted.

DAY FOUR: FANTASTIC BEASTS

The morning’s cold air hit us by surprise — we’d been sweating up to now. As we headed out of town, the first thing most of us did was to turn on our heated grips. What’s the point in getting cold if you don’t have to? Besides, we were in for another long day, which kicked off as normal on a dead straight section of road. By this point we were gagging for adventure, but there was no alternative to riding these roads south.

The rolling pastures became arid, rocky wasteland. We were now in an area called the Great Karoo and it reminded me of the south of Spain. Historically, it had been a vast seabed, but millions of years had seen the water give way to dust, the fish to vervet monkeys. They were everywhere. Around 2ft tall, they had pitch-black faces and silvery bodies. As we rode close to them, they’d run off the road and climb up onto the carriageway-lining jackal fences to keep an eye on us. They were distracting, and so too were the snakes, springbok and baboons that started appearing. We’d only been in the Karoo a few hours, but it already made us feel as if the trip was truly beginning in earnest; this was what we’d come to see.

Another great distraction was the Lootberg Pass. This was the first of 23 passes we were to ride, and its magnificence wasn’t wasted on us as we rode higher and higher towards its summit. From the top, the unrestricted view in all directions was breath-taking. Kudu are among the largest antelopes in Africa. They can run at 70kph and weigh up to 270kg. They’re also really tasty, as we found out at lunch in a farm shop cafe. Just like the price of fuel, food and drink were equally affordable, with most main meals costing just a few pounds.

All dirt roads here start with a few metres of Tarmac. They lure you in and then the road turns to trail, as we found after lunch. Compared to the first dirt route we’d ridden on the trip, this felt effortless to ride fast and with confidence. Our hikes were fitted with Bridgestone’s Battlax A40 rubber, which seemed capable of mastering life on and off-road. We were to ride this particular route for 75km, without any idea of where we were headed, but that element of mystery made life a lot more exciting.

We didn’t need to know where we were going; we needed to know how to get the most from our Tigers on the loose stuff. Before hitting the dirt, the first thing I did was to switch the bike to ‘Off-Road’ mode. This made traction control virtually nonexistent, while switching off the rear ABS. Every now and again a pothole would catch me off-guard, but the bike was otherwise not bothered by the change in terrain. The ride was so much fun, and it got really interesting around 50km in, when we found a railway crossing. Around it were a few abandoned houses, a cattle yard and two churches; our guides explained one would have been for black people and the other for whites. Outposts like this were apparently plentiful, bearing the scars of a time when they had some kind of importance. Now, there was just rust and ruin to show for those forgotten times. It was eerie.

The final stretch of our trail was twisty and more technical. I was riding behind my friend Francesco when his bike dropped into a huge dip where the road had eroded on the far side of a bridge. He was so lucky to stay on board, and we later laughed it off. What was less funny was him running over a snake moments later, not least for the snake.

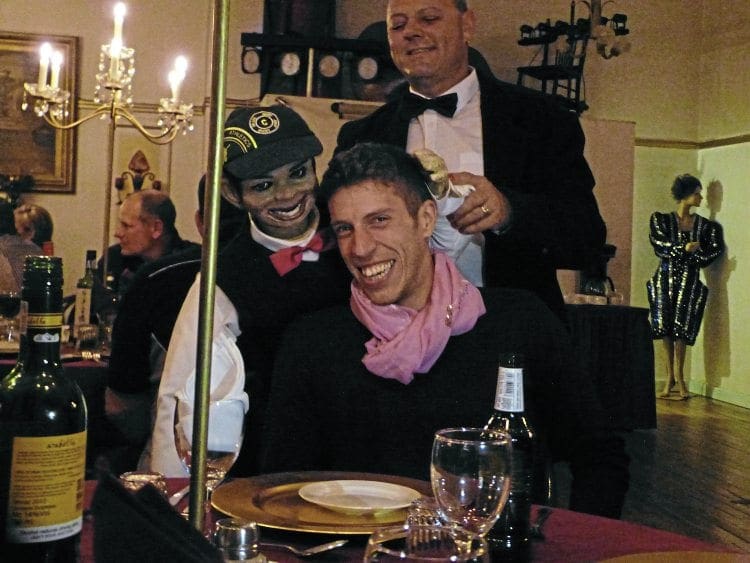

The pace of the group’s riding was still different from man to man, but those less experienced were picking up speed and learning all the time. It was great to see their growth, along with the personalities of our team really coming to life. Having done several long days in the saddle, the organisers had decided to be kind and arranged lodgings at a hotel not too far from the exit of the trail. The place where we were stopping, near Steytlerville, was called the Karoo Theatrical Hotel; one of only three in the world (apparently). We’d got there in good time, so a few beers were sunk and pool was played before the evening’s four course meal and cabaret act began. Having spent a few nights in much more primitive accommodation, the ambience of the hotel was a little perplexing, but not half as much as the drag-act show the hosts had lined up. It was certainly a memorable occasion. Still, nothing could blunt the group’s excitement at reaching the Baviaan mountains the following day. No one had a clue of what to expect, but none of us could wait to find out. The adventure was soon to begin in earnest…

Colourful language

There are 11 official languages in South Africa, and plenty of unofficial ones too. This diverse use of languages paints a strong picture of the nation’s broad history, which incorporates influences from European, Asian and native African speakers. Of the nation’s 50 million inhabitants, the Zulu language has the largest number of official speakers, but English is considered the most universal of all tongues and is the typical choice for business, media and politics.

Going Transvaal

The Dutch word Vaal translates as dull, and was considered the perfect name for South Africa’s second largest river due to its murky colour. It’s a significant geographical feature to the nation, and to this day forms the boundary between Guateng in the north, and Free State in the south.

When the British invaded South Africa, it prompted the original Dutch settlers to ‘trek’ away from the British colonized Western Cape in search of land that didn’t fall under the jurisdiction of the nation’s new rulers. They originally settle in an area known as the Orange Free State, although conflicts with native tribes made life a challenge for the Dutch. The situation was so aggressive that the British intervened and sent a military force into the Free State to safeguard the province.

While some Dutch were grateful of the action, others felt obliged to pack-up their belonging and move north once again. They crossed the Vaal and settled in a land they proclaimed the Boer Republic of Transvaal. By this time the British had withdrawn from policing the Free State, but the discovery of precious gems and metals in the Transvaal was the temptation the British needed to head north and absorb the Transvaal into the Empire in 1877. They argued that the Boers’ mistreatment of black and mix-raced natives was unacceptable, legitimising their reason for annexation. Constant conflict was the consequence, and it wasn’t until 1910 that the British formally absorbed the region into the Union of South Africa.

Concentration camps

The Second Boer War saw the British Empire battle relentlessly for land supremacy with the original Dutch settlers (Boer). As is the case with any conflict, the fighting caused the displacement of families, for which the British established two camps (Pretoria and Bloemfontein) to accommodate the fleeing refugees.

In contrast to later camps, the sites had no guards and the inhabitants saw them as places of security. As the war progressed, and resistance to the occupation increased, the Boer who refused to surrender were forcibly marched to further camps that had begun to spring up all over the nation. The tented or hutted living conditions were ideal for the spread of illness, with measles being a particularly prominent killer. In total, 27,927 inmates died, with the vast majority of these being children.

The Treaty of Vereeniging was signed on May 31, 1902, marking the end of the war and prompting the release of all Boer prisoners, who by now numbered 116,572. Most were destitute, malnourished and displaced from their families. To this day, a large number of the camps are remembered with memorials to mark the inhabitants’ tragedy.

Words & photography: Bruce Wilson