The mysteries of suspension are unravelled with the help of some clever people at K-Tech…

It can be very difficult to obtain that perfect suspension set-up. In racing, with so much adjustability, it can be a challenge to find the compromise between how the bike reacts into a corner, during a corner, and on the exit. In off-road racing and especially motocross, with ever-changing track conditions it’s even trickier. On a stock road motorcycle, built to a specific budget yet designed for a huge range of rider weights (with the option to carry a pillion and luggage) getting it spot-on is understandably an impossible task.

Before riding the project Yamaha XSR700 to Spain, I replaced the standard shock with a £594 K-Tech Razor-R. The OE suspension is okay, but it’s built to a tight budget, and I found it crashy and confused in fast, poorly-surfaced bends, particularly at the rear. The Razor-R transformed it, feeling comfortable and compliant, yet absorbing the harsh bumps that would upset the bike. It was also the first time I’d been able to really feel the changes I made as every couple of clicks to the compression or rebound damping made a noticeable difference to the ride quality.

Enjoy everything MSL by reading the monthly magazine, Subscribe here.

A bike manufacturer has a huge window when designing a standard road machine – from the physically smaller, lighter Asian market, to the often larger US owners. Will the rider be carrying luggage? What kind of road surface will they be on? A bike with too wide adjustment could, in the wrong hands, be set up to handle dangerously – give enough to suit a single Asian rider, and a couple who load their bike up excessively in the States could, theoretically, set the motorcycle to handle dangerously. Due to the litigious times we live in, this could prove costly for manufacturers; hence an average is accommodated for.

It’s this lack of real adjustability that contributes to many riders not believing they understand suspension – until you can actually feel what’s happening as you tweak it, it will always seem something of a dark art.

A lot of OE suspension is set up on the softer side, to be more comfortable. But good suspension, especially when designed around a specific rider, doesn’t have to be harsh. A bike that’s too soft on the front allows the forks to dive too far, changing the geometry and putting more weight over the front tyre, potentially overloading it. It’s all to do with how the bike sits on its suspension – often, firming a bike up will actually make it more comfortable. But it’s not as simple as putting in a stiffer spring – the damping needs to match it. An aftermarket manufacturer like K-Tech can look at an individual rider’s circumstances and riding style to give them an ideal setup and advise them on the correct adjustments.

Some might question why a car can handle anything – from a single driver, to a family of four with luggage – without having to change its suspension (though remember that many manufacturers still suggest changing tyre pressures). Think of it this way – two-up, with luggage, can add 80-90% to the weight of a typical 220kg bike, but a Ford Escort weighs 1150kg. Two adults, two children and 100kg of luggage add less than a quarter of the weight.

Race-bred knowledge

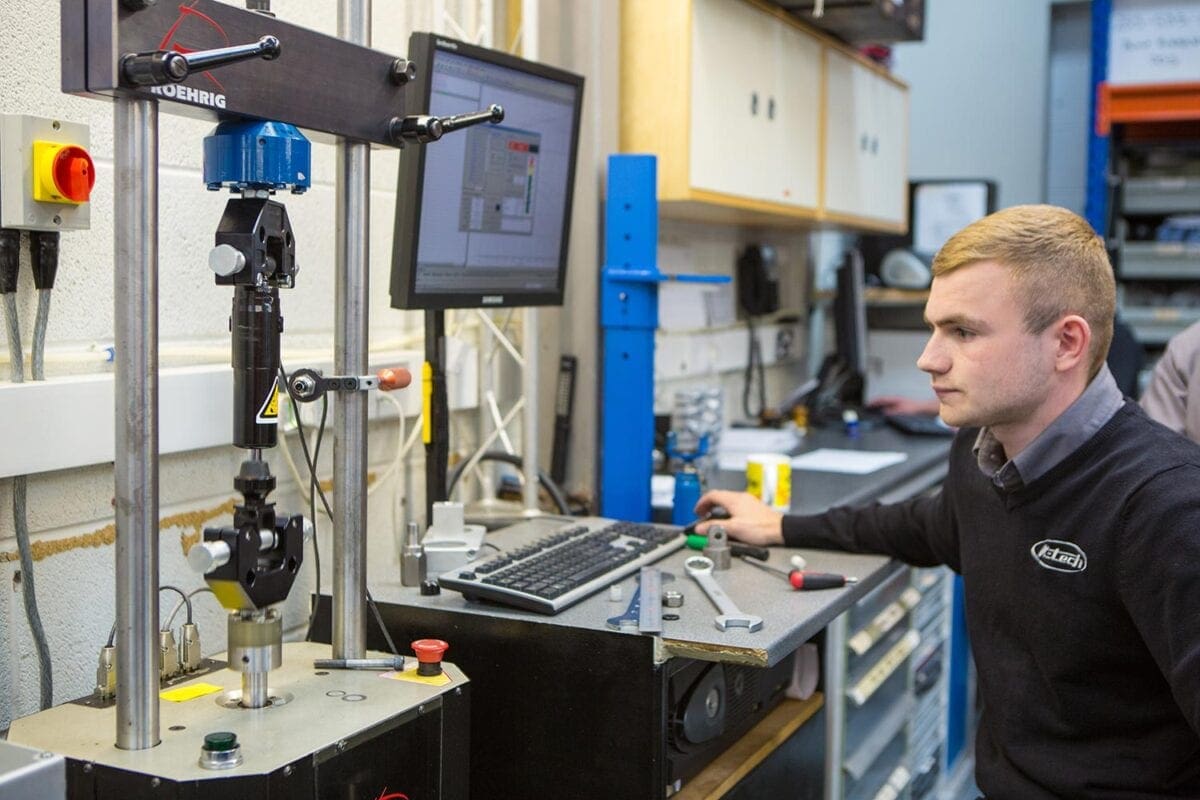

K-Tech was formed by Ken Summerton and Chris Taylor when the pair ran their own suspension businesses and were looking for spring suppliers. They met whilst already working with road and off-road race teams, and brought decades of experience in the engineering industry. Ken had been an aircraft engineer for 20 years, and also worked as a motorcycle mechanic on, among many other things, the cranks from Sheene’s race bikes.

The first K-Tech springs were made in 1994, and by 2001 the company was making front fork piston kits. 2002 saw the introduction of complete racing fork cartridges, which took Fabien Foret to the World Supersport Championship. In 2005 K-Tech developed its first complete fork – the KTR-2 – and in 2007, after listening to the needs of Superstock and Supersport race teams, created the pressurised fork damping systems that would win the 2009 BSB championship.

In 2010, K-tech suspension helped Padgetts and Ian Hutchinson win all five IoM TT races on their Honda CB1000RR with the KTR3 forks. In 2013 the Harley Davidson and custom bike project began expanding the company’s product range, in 2014 Bruce Anstey set the fastest lap at the TT, and Guy Martin’s Pikes Peak Challenge was supported by K-Tech. Hutchy dominated all three road-racing events in 2015 on K-Tech, and in 2016 won the Supersport 600 and Super Stock 1000 races with Ian Hutchinson, amongst many other podiums.

“We’re still only 20 people, but we’ve got around 60% of the paddock in BSB alone,” Ken told me. “But we’re now doing far more than race kit, and our shocks include twin-shocks, and the new Bullit air-shock units.”

While there’s a network of dealers supplying, fitting and adjusting K-Tech kit, the company is still approachable and happy to help – there will always be a workshop at the factory for people who need some help or advice; “It’s really important, even as we grow, that customers have access to the manufacturer.”

K-Tech develops and builds road and race suspension for most bikes, but also carries spares for – and offers servicing of – almost any brand; Öhlins, WP, Showa, Kayaba etc. OE suspension can often be rebuilt (the cheapest has peened-over canisters that can’t be opened) and K-Tech will service it. Ken explains; “You’d put new engine oil in your bike after a year, but people forget that as many times as your engine’s internals are moving, so are the components in your suspension. On a road bike, I’d recommend servicing suspension every two years – changing the oil alone makes a massive difference. At the end of the day, it’s oil and a few rubbing parts… something’s going to wear.”

What does what

A machine like the XSR700 – or indeed the new Tracer 700 – has no piston in the fork – it’s a ‘viscocity damping fork’ that is simply an inner tube with holes in the bottom going through an outer tube with oil in it. Fitting a more advanced cartridge fork system doesn’t just introduce adjustability, it has a much better control of the oil, using a regulator valve that limits the flow of oil displaced as the inner piston moves. There’s also a shim stack fitted to the piston, which is basically several thin steel discs that can deflect under higher pressures, reducing the resistance of the piston in the oil by opening up holes machined into it (this is what allows the fork to be more compliant when hitting harsh bumps that cause the fork to move faster) – it’s basically the same in a rear shock. Good suspension will give more comfort, more feedback and more control.

A motorcycle works best as a balance, so it’s typically ideal to improve the front and rear of a bike, but people often tend to change the front first as it’s what they feel most. The XSR just had a new shock, which made a very noticeable difference.

Suspension is simply the connection between the tyre and the vehicle, controlling sprung mass. The spring, be it in your fork or on your shock, controls the mass of the bike. The damping controls the speed at which the spring is allowed to move. Here’s what you need to know…

Preload: This is the most misunderstood part of suspension. Increasing preload does not make a spring ‘stiffer’, it simply increases the ride height of the bike. However, it does affect the break-out force – the point at which it starts to move. If you have a 100lb/inch spring, and you put one inch of preload on it, to make it move you have to add another 100lb. Once it’s moving it feels the same, as the spring rate is unchanged, but this increased break-out force can make a bike feel more harsh as greater loads are transferred to the rider before the spring starts to react. Equally, if you add 50lbs of luggage to a bike with a 100lb spring that is balanced to you as a solo rider, an additional half an inch of preload will even out the additional weight and maintain the correct static sag.

Increasing the ride height can speed up the steering (something I found helpful on the Bonneville T120 launch), but in order to do this without increasing the preload, many aftermarket shocks like the Razor-R come with an adjuster that lengthens the shock without compressing the spring.

Static sag: This is the amount the bike drops as the spring takes the weight. It’s the difference in height between the machine sitting naturally, and the bike being lifted to the point where the wheel is only just touching the floor. Sag allows the wheel to drop into dips in the road surface without taking the bike with it – it’s simply slack in the suspension. Picture a Dakar racer blasting across sand dunes – the bike stays level over dips while the wheels drop into them because of sag.

Air gap: Air acts as a spring and is generally also part of a fork’s characteristic. It’s simply the space between the top of the oil and the fork cap. Air can also be used to replace a spring altogether, as in K-Tech’s Bullit units designed for bikes like the Ducati Scrambler, Harleys, Indians and more. Like the oleo struts used in tanks and aircraft landing gear, these nitrogen-charged shocks give constant damping control over a wide range of loads and surfaces.

Progressive spring: These are simply springs that get stiffer as they’re compressed further, making them return more force as the suspension increases its stroke.

Progressive link: Also known as ‘rising rate’, the link joins the swingarm to the shock, and causes it to require more force to be moved as the suspension is compressed. As with a progressive spring, the principal is to allow a softer feel under normal conditions, without letting the suspension bottom out.

Compression damping: Oil inside the fork or shock restricts movement to slow the speed at which the spring is compressed. Too little and the spring’s movement is uncontrolled, too much and it’ll create a harsh feel as the component can’t move smoothly.

Rebound damping: This controls how quickly the suspension can unload. Too little and the bike will bounce back from a compressed state. Too much and the suspension can ‘ratchet down’; imagine riding over a series of close bumps with too much rebound damping on the rear shock – the tail of the bike will never get time to return to its natural position, and get quickly lower until you’re kicked up the bum. This could be reduced by decreasing the amount it moves in the first place with more compression damping, but then the ride would be a lot harsher.

Suspension is all about the balance of all the settings, so for the very best ride, the spring has to be strong enough to support the weight of the bike and its rider. Then the damping needs to be set to control the force of that spring, and to give the level of comfort and performance needed for the riding conditions. Put simply, the spring dictates the position of the bike, the damping controls the speed at which it moves.

Electronic suspension: There’s still a spring and damping arrangement, but sensors analyse the way the bike moves to allow servos to adjust the damping based on varying conditions. Many racers opt not to use it as a track doesn’t have the hump-back bridges (besides Cadwell), pot-holes and other imperfections that make a road surface unpredictable, but it’s also not allowed in closed-circuit racing at national and international competitions as it’s banned by the controlling body. And they won’t be carrying a pillion or loading the bike up with luggage. Semi-active will adjust the suspension after it’s felt the road surface (so after you’ve been through a pot-hole); active suspension reacts to the surface as it happens. Theoretically, a well-programmed active system could be the perfect set-up with no compromises.

So is it essential to change your bike’s suspension? Not at all – if it feels great to you, then don’t let anyone tell you otherwise. However, good suspension can make a world of difference to a bike’s comfort and handling. Is it worth the money over, say, a new exhaust? Deputy Editor and Endurance racing champion Bruce Wilson put it well: “None of us ride flat out on the road, so a good handling bike is far more useful than a powerful bike.”

Motorcycle Sport & Leisure magazine is the original and best bike mag. Established in 1962, you can pick up a copy in all good newsagents & supermarkets, or online…

[su_button url=”http://www.classicmagazines.co.uk/issue/MSL” target=”blank” style=”glass”]Buy a digital or print edition[/su_button] [su_button url=”http://www.classicmagazines.co.uk/subscription/MSL/motorcycle-sport-leisure” target=”blank” style=”glass” background=”#ef362d”]Subscribe to MSL[/su_button]